Chord Progressions

If you've never heard the Four Chord Song by Axis of Awesome, watch that first.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5pidokakU4I

The comedy song is funny because there are so many songs that sound the same. There is even a list on Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_songs_containing_the_I–V–vi–IV_progression

In this article, I'll try to answer 3 questions.

1. Why do some songs sound the same?

Disclaimer: I can't play an instrument, and everything I know about music theory is written in this blog post.

1. Why do some songs sound the same?

Music is not random. The links in the title talk about the I–V–vi–IV progression, but that's not the only common chord progression.

The 2.4.1.5 II-IV-I-V "Wonderwall" progression has some of my favourite songs.

Forget December - Something Corporate, Gone Away - The Offspring, and New Divide - Linkin Park.Other songs that sound similar include:

Maneater - Hall & Oates, Part Time Lover - Stevie Wonder.

There's a list of Suspiciously Similar Songs.

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/SuspiciouslySimilarSong/Music

a. Parsons Code

Listen to a song you like, and drum your fingers.

I'm using my right hand to represent the chord progression, even though I can't play an instrument.

I can "play" 4 different "notes" using my hand: index finger, middle finger, ring finger, and little finger.

When the "note" sounds "higher", I tap a finger on the right (towards the little finger), "up".

When the "note" sounds "lower", I tap a finger on the left (towards the thumb), "down".

When the "note" sounds the same, I tap the same finger again, "repeat".

This is called Parsons Code.

There are 3 possibilities: up, down, or repeat.

We learned from Axis Of Awesome that most songs use 4 chords.

If you generate all the possibilities (ParsonsAll.txt in my dataset), there are 81 Parsons codes.

rrrr

rrrd

...

dudu

...

uuuu

That means every song in the world sounds like one of those 81 codes!

Not so many, right? Why not generate all of them, listen to choose the ones I like, and find more songs!

That's covered in my answers to questions 2 and 3. It gets more complicated, as we will see.

b. Notes

What if there's a difference between going "up" a lot and "up" a little?

To understand this, we need to learn some basic music theory.

It will help to have the Scientific Pitch Notation table open in another tab.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_pitch_notation#Table_of_note_frequencies

There are 12 "levels" - C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B. These "levels" are called "notes".

For some reason I don't totally understand, some have 2 names (e.g. C#=Db, D#=Eb, F#=Gb, A#=Bb).

There is also no E#. It just doesn't exist. Get used to it. Those are the 12 notes.

Edit 2025-06-22: Christian Van Simaeys emailed to clarify!

He explained that C#=Db, D#=Eb, F#=Gb, A#=Bb is so for keyboard players but not for String players.

The distance between 2 notes, take C and D (1 interval), is divided in 9 equal parts (frequencies) (in French called "virgule" meaning comma).

C# is 5 comma higher then C

Db is 5 commas lower than D

this means that between C# and Db there is 1 comma difference aka 1/9 of the difference between C and D

String players can and will play this difference. Keyboards can't because their keys are tuned to the same frequency.

c. Octaves

Haha, they aren't only 12 notes.

The pattern of the 12 notes repeats and wraps around (after the last B there's another C, then C#, and so on).

You can move up an "Octave", which means going from one "C" to the next "C", which is 12 notes higher.

MIDI is a wonderful computer standard that makes all the notes fit into 128 numbers.

There are 11 possible notes called "C" that can be represented in MIDI.

d. Chords

Musicians never play notes one at a time. They always use chords.

A chord is 3 notes played at the same time.

There is a chord called "C major", but it's totally different to the note called "C".

The notes in "C" are C,E,G.

There's also a chord called "C minor".

The notes in "Cm" are C,D#,G.

Remember that D#=Eb (section 1.b. of this article)?

You can also say that the notes in the chord "Cm" are C,Eb,G.

There's also 7th chords, Augmented chords (+), and Diminished (º) chords.

As far as we're concerned, there's a lookup table that lets us turn these chords into notes.

Thank you to Yi-Shing Chung for helping me to understand notes and chords!

e. Roman Numerals

Finally we can understand what the I–V–vi–IV progression means!

There are 7 different Roman Numerals. The uppercase/lowercase doesn't matter.

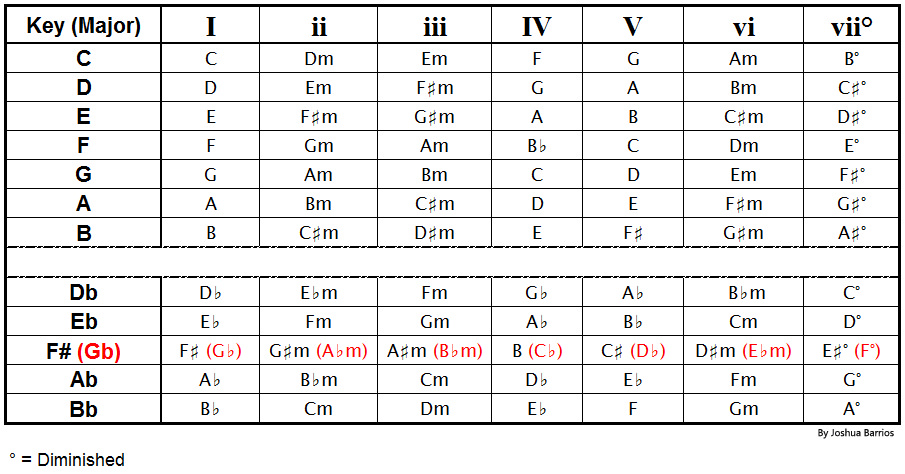

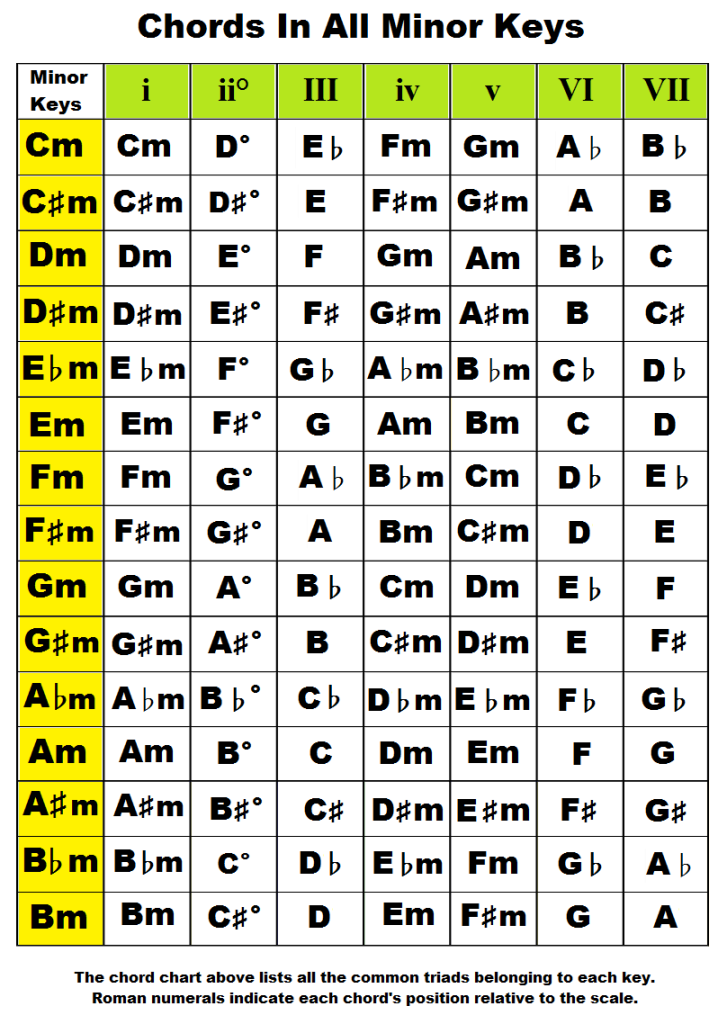

For a "major key", the Roman Numerals are: I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, viiº.

For a "minor key", the Roman Numerals are: i, iiº, III, iv, v, VI, VII.

Let's just use numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7.

I–V–vi–IV means 1.5.6.4.

f. Chord Progressions

We just learned that I–V–vi–IV is a common chord progression, and it can also be written 1.5.6.4.

If you want to find similar songs, you can search the HookTheory database. Just put the numbers into the URL.

https://www.hooktheory.com/trends#node=1.5.6.4&key=C

For a four-chord song, we can make all the possibilities:

1.1.1.1

1.1.1.2

...

1.5.6.4

...

7.7.7.7

There are 2401 possible chord progressions. That's still not so many. Let's generate them all!

The list is in ChordProgressionsAll.txt.

If you know the chord progression and want to know the Parsons code, that data is in Parsons Chord Progressions.txt.

g. Key

To get the notes, we need to know the chords.

To get the chords, we need to know the Roman Numerals and the key.

What's a key?

The chord progression 1.5.6.4 = I–V–vi–IV in the "key of C" is C-G-Am-F.

In the "key of G", 1.5.6.4 is the chords G-D-Em-C.

If you change from one "key" to another, you "transpose" the chords.

It is possible to "transpose" chords to Roman Numerals, or Roman Numerals to chords.

It is also possible to transpose from a "minor key" to a "major key". That turns sad songs into happy songs.

http://theweek.com/articles/467109/sad-songs-made-happy-amazing-art-turning-minorkey-songs-major

There are 30 possible keys:

"A", "Am", "Ab", "Abm", "A#m", "B", "Bm", "Bb", "Bbm", "C", "Cm", "C#", "C#m", "Cb", "D", "Dm", "D#m", "Db", "E", "Em", "Eb", "Ebm", "F", "Fm", "F#", "F#m", "G", "Gm", "Gb", "G#m".

When you transpose, you actually shift the base line of the Scientific Pitch Notation table from 1.b.

That table is in the key of "C". The table goes from C to B. It looks like "D" is "higher" than "C".

But if you transpose the table, then the table goes from "D" to "C". Now "D" is "lower" than "C".

There are some problems when moving the MIDI table, because some notes don't exist in the lowest or highest octave.

Every note in every key exists in at least 7 octaves. You can't really hear the high and low octaves anyway.

If you don't transpose the table, the Parsons code for a chord progression will be different when changing the key.

That means it sounds different, which can't be right. So we must transpose the chord table first.

Thank you to Lenard Chuang for helping me figure out how to transpose correctly!

Now let's go back to the Parsons code.

I generated all the Parsons codes for all the possible chord progressions.

See the ProgressionsByParsons folder for this data.

Some Parsons codes have more chord progressions (dudu and udud).

What's weird is that some possible Parsons codes (e.g. ruur) are not possible using standard chord progressions.

That data is in ParsonsOnlyTheoretical.txt.

All the Parsons codes that are actually used in chord progressions are in ParsonsReal.txt.

h. Summary

"C" can mean 3 different things: a note, a chord, and a key. They're totally different to each other.

We have 30 keys * 7 octaves = 210 ways to play the same chord progression.

We also have 2401 chord progressions.

So that's a total of 504,210 tunes.

Let's generate them all!

2. Can I find new songs that go well together?

a. Cheer me up

Closing Time - Semisonic and All Star - Smash Mouth sound really similar, and make a great mashup.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tZNaNfAzfIA

This is because they use the same chord progression (see section 1.f).

You can make a playlist to using same chord progression in a minor key, moving to similar songs in a major key (see section 1.g)

That should have the effect of cheering you up - making you feel happy.

b. Compare chord progressions

For songs in the same key, you can just compare the chords.

If the songs are in a different key, you can't compare the chords directly - you have to know the key, and then transpose to Roman Numerals.

If you don't know the key, you can't transpose even if you know the chords.

If you only have an MP3, this problem is "hard". Extracting chords is usually done by hand by talented musicians.

Sometimes even the experts don't know what chord is being played, e.g. A Hard Days Night - The Beatles.

c. Extracting chords from MP3s

Existing software to take an MP3 and generate chords doesn't work well. Instruments interfere with each other, and frequencies are all over the spectrum.

Melodyne doesn't get the chords - only the notes. Each chord is made of 3 notes. Then you need to figure out the chords from the notes.

It's helpful for figuring out a Parsons code, but it's slow and wouldn't be able to process my large iTunes library.

Melodyne also uses a lot of ad-tracking cookies, so you'll see their adverts everywhere on the Internet if you visit their page. You have been warned.

http://www.celemony.com/en/melodyne/what-can-melodyne-do

Capo is a program that uses machine learning to try to guess chords. I tried it briefly, but got very different results to some human-written chord charts.

http://supermegaultragroovy.com/products/capo/mac/

Shazam can search a large database of MP3s using audio fingerprints and machine learning. This isn't analysing chords, but it can handle the large databases of MP3s.

How does it work? There's a technical article about that by Christophe:

d. Comparing frequencies

If you want to write your own chord analyser, you can use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to find the loudest frequencies.

You can then compare the frequencies with the notes in the Scientific Pitch Notation table.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_pitch_notation#Table_of_note_frequencies

I think this is how Melodyne works.

If an instrument is not tuned correctly, the frequencies will be a bit different than they should be in order to get a certain note.

I don't know about the different tunings (e.g. drop-D on a guitar), and how they affect the data here. That's an area I'd need to research some more.

The frequencies for all 2401 possible chord progressions are listed in the Frequencies folder.

3. How do we use music theory to improve machine learning?

a. How machine learning works

If you have lots of examples of something, machine learning can automatically look for patterns.

A machine learning program is also called a "neural net".

The "neural net" must be "trained" by putting in a lot of sorted examples.

You need to have structured data.

For example, Blink 182 and The Offspring are both "Rock". If I like Blink 182, I like "Rock". Therefore maybe I will also like The Offspring.

That is how Spotify recommends music - by looking at other people's playlists and telling you what they like.

There is an audio model used by Spotify, but it is measuring "time signature, key, mode, tempo, and loudness" - not chord progression.

Make playlists for "Rock", "Pop", "Dance", "Rap", and "Classical", and if you've got enough examples, it's probably possible to suggest some good music.

But it won't always give you a good mix. Even some songs by the same artist can be different.

If I listen to The Unwinding Cable Car - Anberlin (a slow song), I don't want to hear Audrey, Start The Revolution - Anberlin (a fast song) right after.

Both songs are Rock, both have the same artist, but they're emotionally very different.

b. Getting structured data

In section 1.h, I decided to generate 504,210 examples: 210 key/octaves for 2401 chord progressions.

That is highly structured data, and excellent for machine learning.

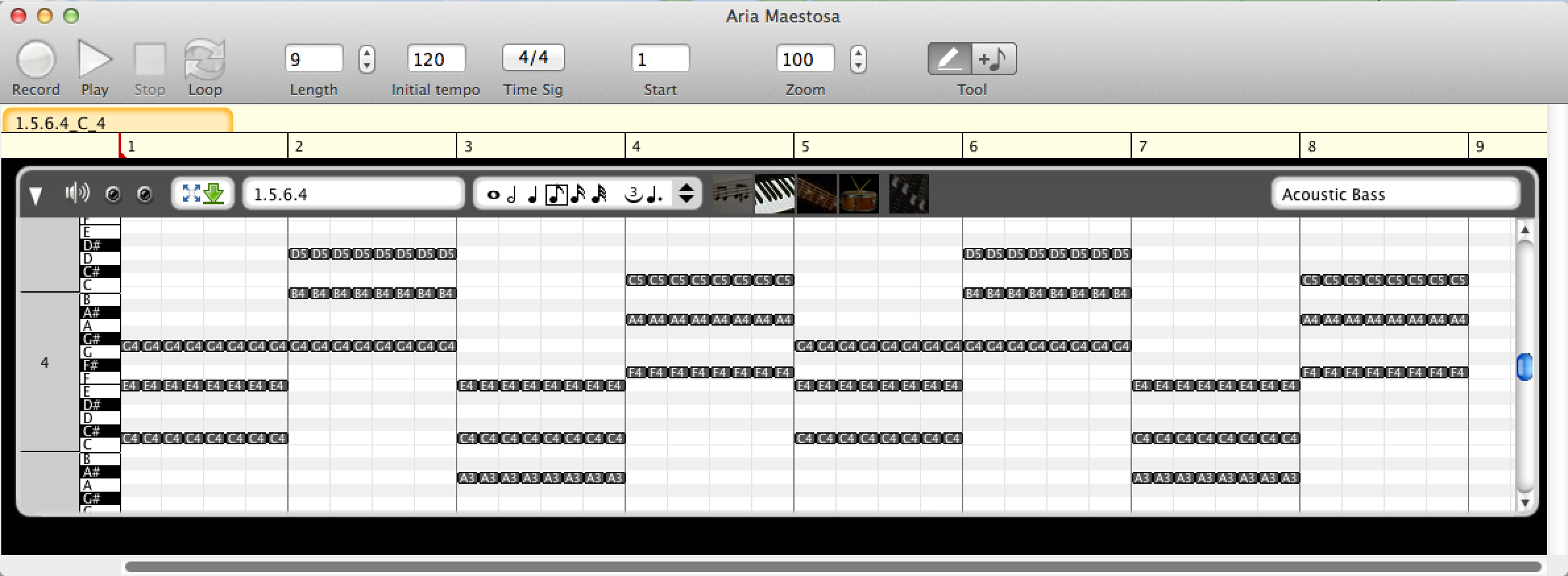

To build the data, I wrote an AppleScript to generate CSV files for every tune.

Each chord is played for 8 beats of 80 ms. I don't know why I chose that, it just sounds right.

This is what the "udud" Parsons code "looks like". As you can see, each chord is played 8 times, then it changes.

________--------________--------

I then converted the CSV files to MID using midicsv-1.1 by John Walker.

http://www.fourmilab.ch/webtools/midicsv/#Download

If you want to see that pattern, you can edit the MID file using Aria Maestosa.

http://ariamaestosa.sourceforge.net

The total size of the CSV files is over 5 GB uncompressed, or 600 MB compressed. The MID files are 2 GB uncompressed.

The MID files are 8.3 MB compressed as a tar.bz2 file.

Therefore I'm only uploading the MID files as MID.tar.bz2.

c. Converting MID to MP3

Be warned - you need a lot of disk space!

One chord progression will generate 210 files (one for each key). That's 1.5 GB of WAV, or 100 MB of MP3 per progression.

All 2401 chord progressions therefore require about 234 GB of disk space.

That's why I'm not uploading MP3 files.

A MID file just describes the chords. It doesn't choose an instrument for you.

You need to download some instruments. I used a collection of 259 instruments called "generaluser", which is a strange name.

http://www.schristiancollins.com/generaluser.php

If you want to play a MID file, just open it using VLC or (the old) QuickTime Player 7.

If you want to convert MID to WAV, use Fluidsynth.

Then to convert WAV to MP3, use Lame.

The commands to convert to WAV and then MP3 are as follows:

/opt/local/bin/fluidsynth -F "ChordProgressions/WAV/1.5.6.4_C_4.wav" -i /usr/local/share/fluidsynth/generaluser.v.1.471.sf2 "ChordProgressions/MID/1.5.6.4_C_4.mid"

/usr/local/bin/lame --preset standard "ChordProgressions/WAV/1.5.6.4_C_4.wav" "ChordProgressions/MP3/1.5.6.4_C_4.mp3"

d. Separating instruments from a track

If example data can be generated for every instrument, it should be possible to use machine learning to split an MP3 into different instruments.

For all 2401 chord progressions played by all 259 instruments in MP3 format, that's 60 TB of data.

This data is huge.

Currently, musicians have to use a multi-track recorder. There's no way to split a single track into each instrument.

This type of audio-based machine learning might allow instrument tracks to be split out from an MP3.

That's beyond the scope of this article, though, and I'm still learning Tensorflow. I hope someone on Kaggle can help.

e. I forgot something

That's probably true! Music is much more complicated, and there are arpeggios, 3-chord progressions, the 12-bar blues, and much more to discuss.

The purpose of this article is to share what I understand about basic music theory so computer programmers can know what's going on.

The MID data for chord progressions is provided so that machine learning experts can improve the audio models that analyse songs.

I hope that with new technology, we can teach a computer how to drum its fingers.

f. File list and brief description

| ChordProgressions.zip - The whole dataset. |

| Chord Progressions.scpt - The AppleScript program used to generate all the data. Contains Chord-MIDI-CSV, transposing, and Parsons code functions. |

| ChordProgressionsAll.txt - A list of all the possible chord progressions. |

| csvFoldersToMid.sh - A shell script to convert CSV to MID. |

| csvmidi - Binary of a program by John Walker that converts CSV to MID, described in section 3.b. |

| Frequencies |

| Frequencies.zip - The frequencies for all the chord progressions in every key and octave. | ||

| 1.1.1.1.txt | ||

| ... | ||

| 7.7.7.7.txt | ||

| MIDI Frequencies.txt - A list of MIDI notes and the frequencies. Useful if you have a spectrum analyser and want to find a note. |

| Images | |

| 1.5.6.4_C_4 Aria.png - An example MID file as displayed in Aria Maestosa, see section 3.b. | |

| Chords and Keys.jpg - Lookup table for chords and major keys to Roman Numerals | |

| CircleofFifths.png - Minor/Major key conversion. | |

| music_chords_in_the_key_of_a_b_c_d_e_f_g_flat_sharp_minor-727x1024.png - Lookup table for chords and minor keys to Roman Numerals | |

| roman-numeral-system-in-music-theory.png - Another major/minor table. |

| MID.tar.bz2 - The data we are interested in. It uses about 2 GB uncompressed, please make sure you have enough disk space. | ||

| 1.1.1.1 - A folder for all possible chord progressions. | ||

| ... | ||

| 1.5.6.4 | ||

| 1.5.6.4_A_1.mid - The chord progression 1.5.6.4 I-V-vi-IV, in the key of A, MIDI octave 1. | ||

| ... | ||

| 1.5.6.4_C_4.mid - The chord progression 1.5.6.4 I-V-vi-IV, in the key of C, MIDI octave 4. | ||

| ... | ||

| 1.5.6.4_Gm_7.mid - The chord progression 1.5.6.4 I-V-vi-IV, in the key of Gm, MIDI octave 7. | ||

| ... | ||

| 7.7.7.7 |

| midicsv-1.1 - Source code of a program by John Walker that converts CSV to MID, described in section 3.b. |

| Notes | |

| Four Chords.txt - Rough notes and some lookup tables | |

| ii-iv-i-v.txt - More examples of songs |

| Parsons | ||

| ParsonsAll.txt - All possible Parsons codes | ||

| ParsonsByProgression | ||

| 1.1.1.1 - The Parsons code for each chord progression (it is the same in every key) | ||

| ... | ||

| 7.7.7.7 | ||

| ParsonsOnlyTheoretical.txt - No chord progressions have these Parsons codes. | ||

| ParsonsReal.txt - At least one chord progression follows these Parsons codes. | ||

| ProgressionsByParsons | ||

| dddu - A list of chord progressions that follow the Parsons code dddu. | ||

| ... | ||

| uuud |

| ReadMe.txt - This document |

| Wikipedia MIDI Chord Progressions - 130 of the most common chord progressions from Wikipedia. |